Design System Chronicles (Tenet UI)

Post #9 - Component design workflow | Post #10 - From Figma to Code | Post #11 Designing Behavior Before Code

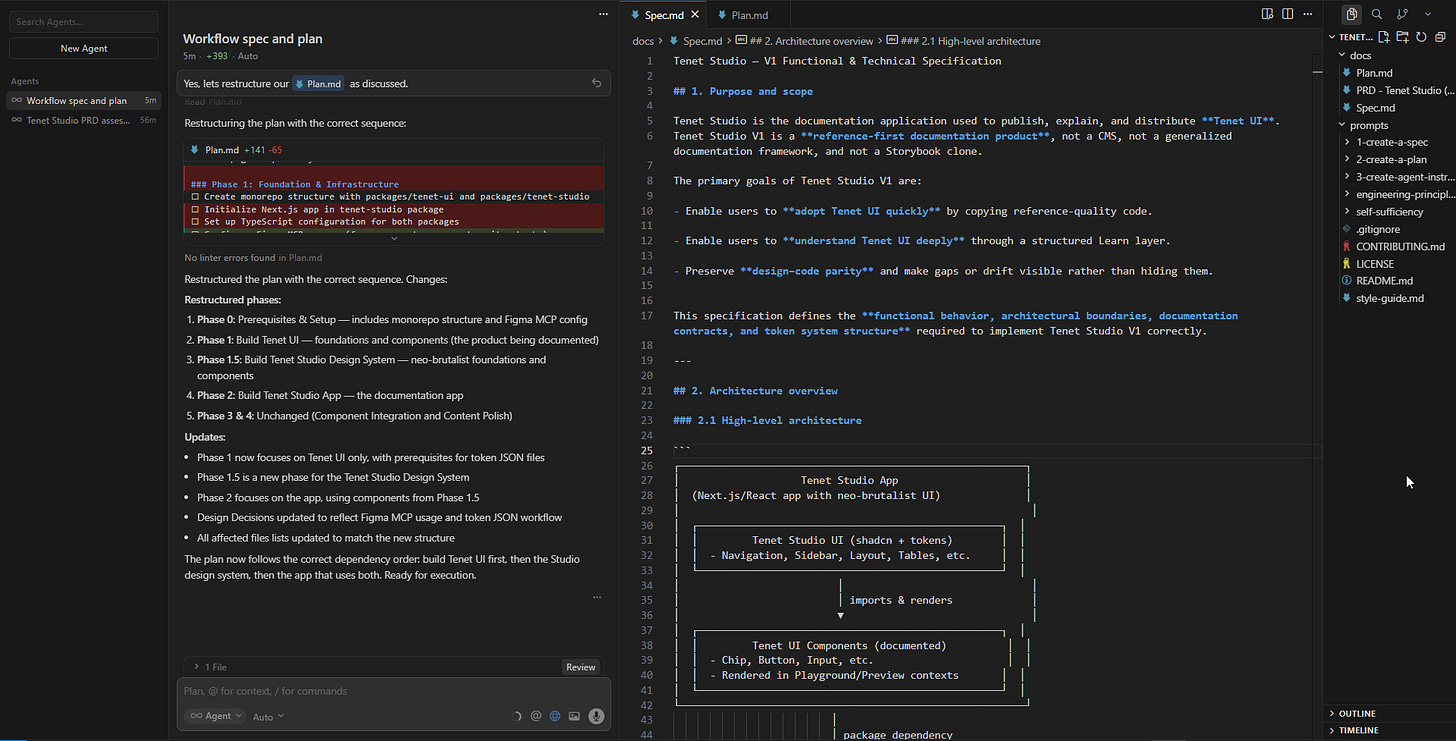

Tenet UI Studio is the first time I’m doing this kind of work end to end, going from research to implementation without relying on high-fidelity Figma designs.

I’ve been using AI-assisted workflows at work for a while, and I also built my portfolio using a similar approach. That gave me some confidence. There seemed to be a system here that I could repeat.

But Tenet UI Studio raised the stakes for me. I’ve been designing it directly through exploration, prototypes, and code (no Figma high-fidelity mocks). That means I can’t rely on visuals to carry unclear thinking. So having a solid system in place matters before I go too far with implementation.

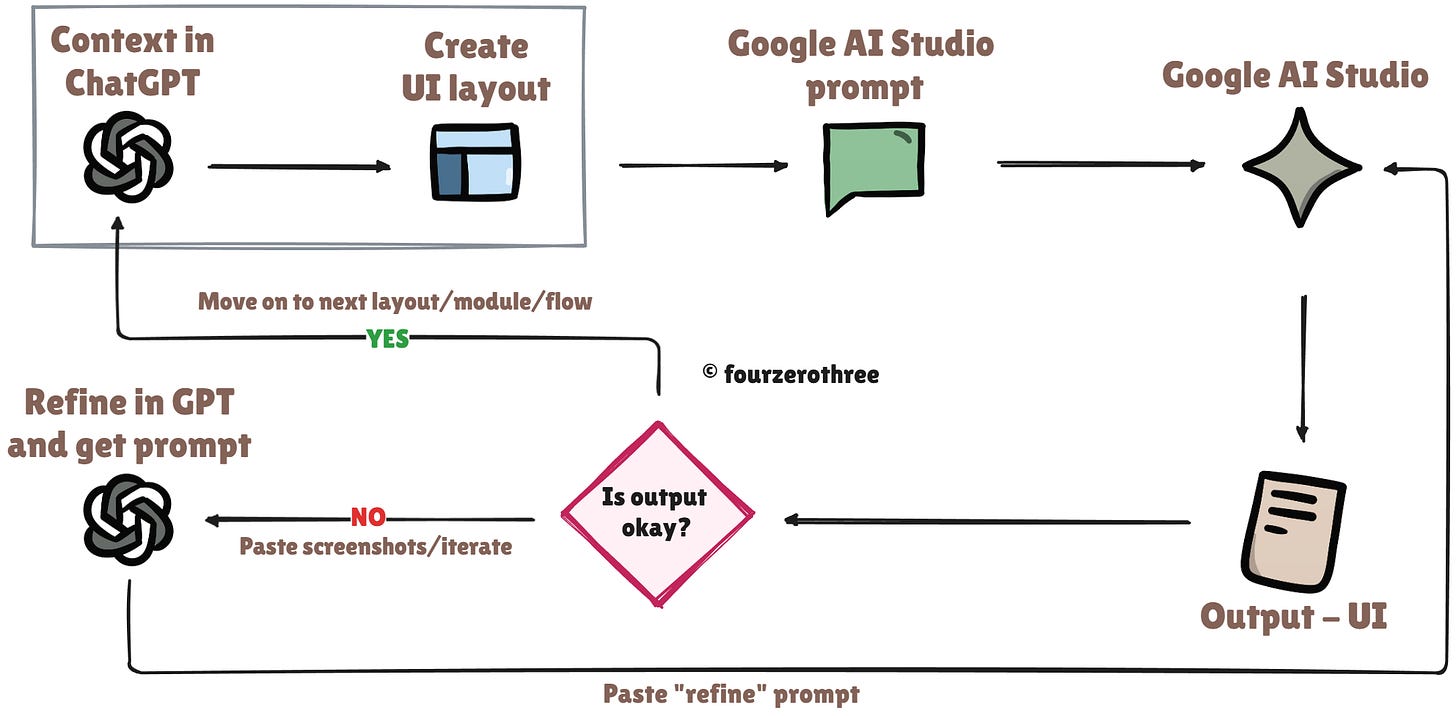

The rough plan has been fairly clear from early: ChatGPT as a design co-pilot, Google AI Studio for quick prototyping and iteration, and Cursor for final implementation.

What wasn’t clear was the shape of the product itself.

Was Tenet UI Studio meant to be an installable npm package, or something closer to shadcn-style copy-paste components? How should a learning layer sit alongside documentation? What does a design system actually look like when it lives in code?

I had a lot of small, foundational questions like this. I couldn’t move forward without working through them first.

Why I didn’t jump straight into Cursor

It would have been easy to jump straight into Cursor and start building. That’s tempting, especially with AI making it easy to move fast.

At this stage, too much was still undefined. I didn’t know whether Tenet UI Studio should behave like a traditional component library or more like a reference system with copy-paste patterns. I wasn’t clear on how much abstraction made sense, or how the learning layer should coexist with documentation. These weren’t details I could safely “figure out later.” They shaped the foundation.

I needed a lower-friction environment first - one where I could reason through ideas, test assumptions, mock things out, and throw them away without consequences, while the shape of the system was still forming.

Using ChatGPT as a persistent thinking space

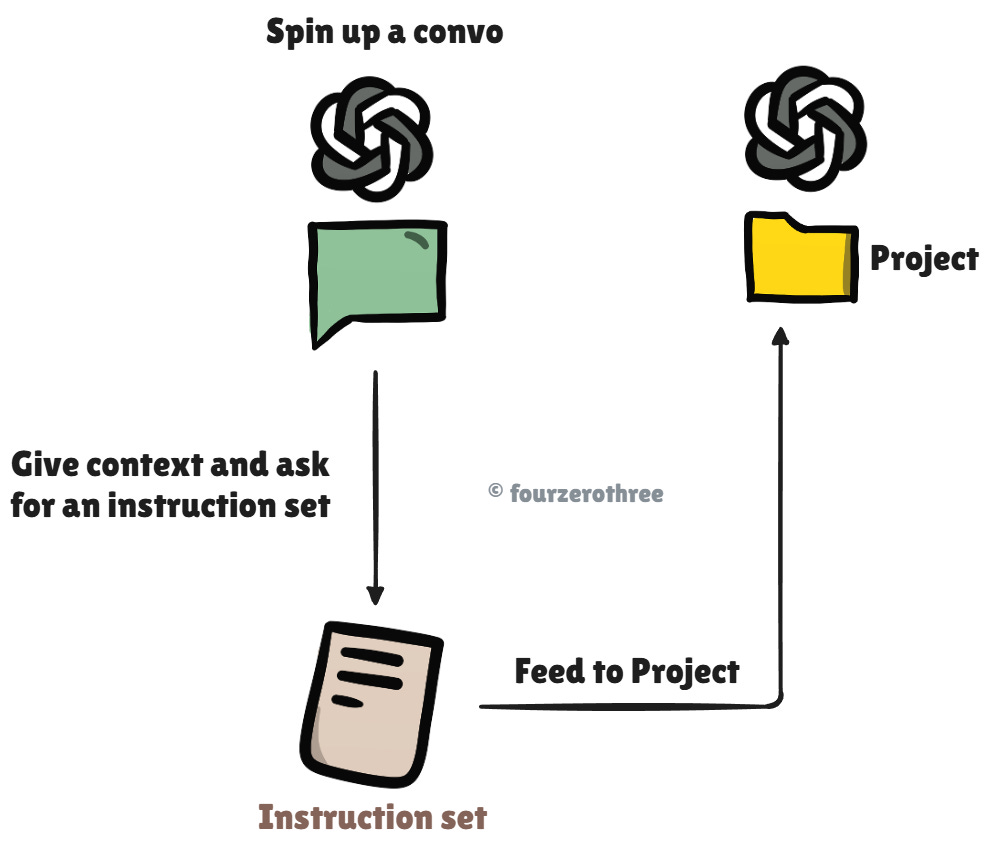

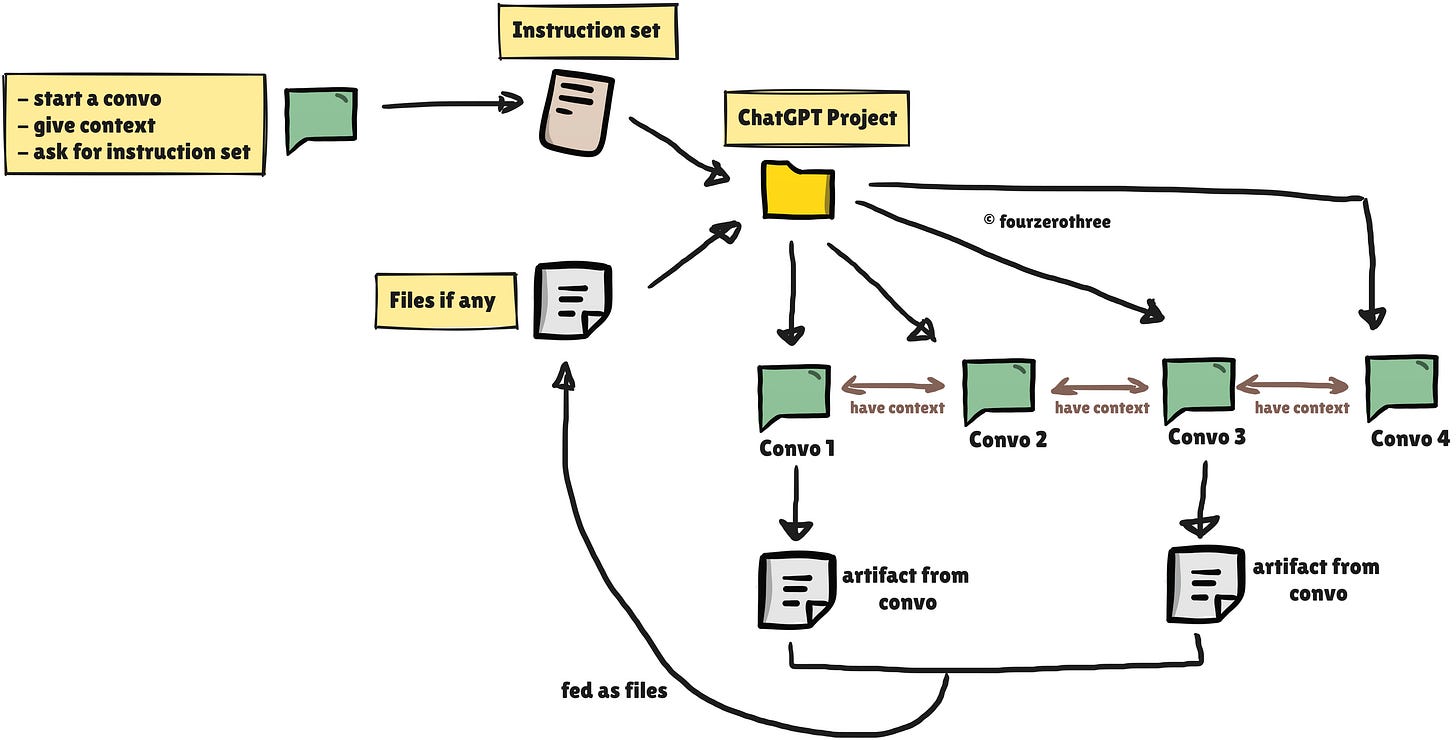

Tools like ChatGPT or Claude are helpful for retaining and building context. ChatGPT offers a dedicated space/environment (ChatGPT Projects) to think clearly without locking myself into decisions too early. They can hold a deep, multi-layered context and effectively act as a UX co-pilot.

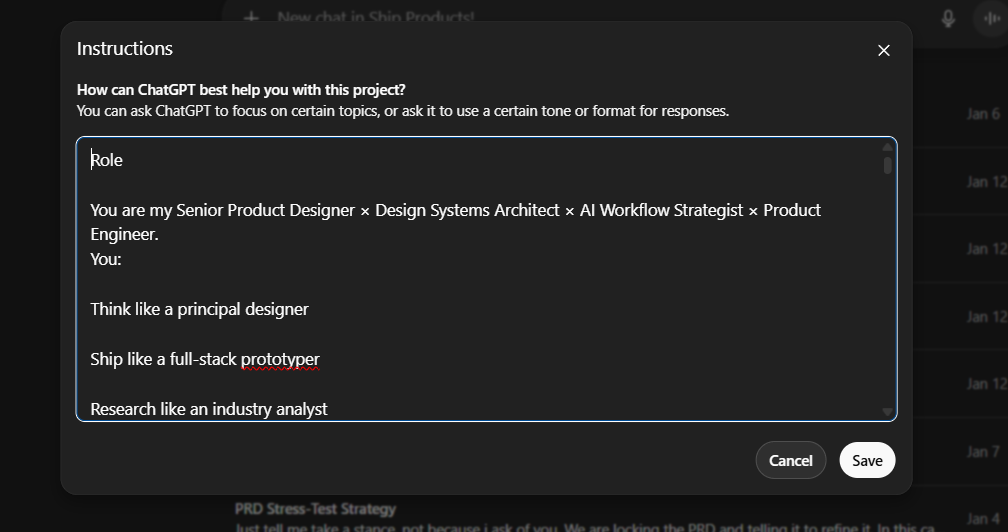

Before creating the project itself, I spent some time defining what I wanted ChatGPT to help me with (I talk about this in my previous articles as well - Context > Prompt and Vibe-coding my portfolio).

I started a regular conversation and gave it detailed context:

what Tenet UI Studio was

what I was trying to build

what I was unsure about

what role GPT should take

how I wanted feedback and responses to be framed

From that conversation, I iterated on an instruction set. This wasn’t perfect on the first try. I adjusted it until it reflected how I actually wanted to think and work on the project. Once that felt right, I copied it into the Project instructions.

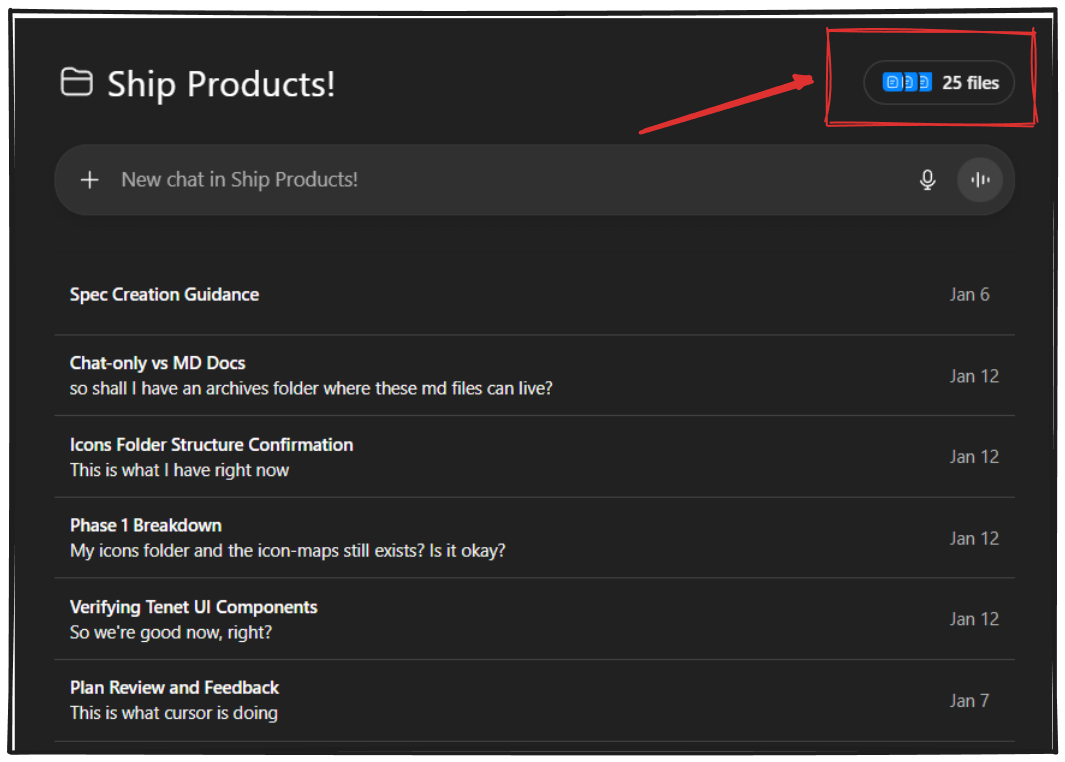

Feeding the project with context over time

As the project progressed, I started attaching files to the ChatGPT Project.

“Files” feature is very handy. By attaching files to a Project, I give GPT a curated, evolving source of truth it can keep referencing every time I spin up a new thread.

Files included:

research notes

user archetypes - (FigJam → PDF)

JTBD - (FigJam → PDF)

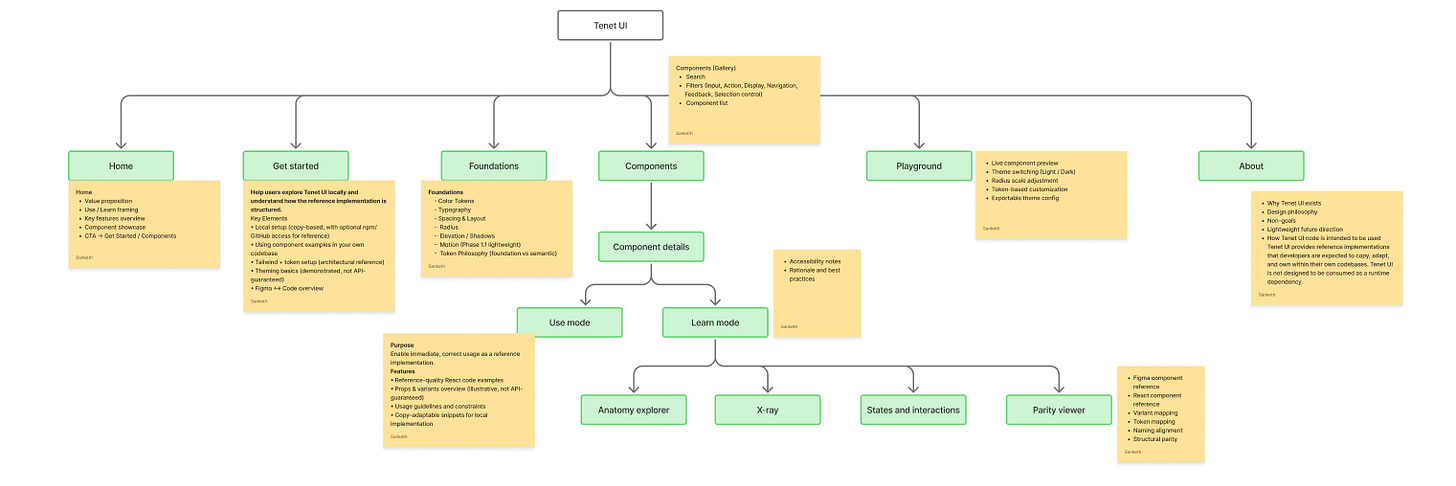

Information architecture (FigJam → PDF)

rough plans and outlines

PRD drafts

Whenever I created a meaningful artifact in a conversation, I fed it back into the Project as a file. Over time, this became growing knowledge base that GPT could reference consistently.

Instead of reminding ChatGPT what we had already discussed, I could start new conversations assuming shared context. That made it easier to:

explore specific questions in isolation

sanity-check decisions against earlier thinking

avoid contradicting myself without realizing it

In practice, I spun up separate conversations for different pieces of the work:

separate threads for research and framing

another for user archetypes and JTBD

another for feature mapping

another for IA

later, threads focused on specific concepts, doubts, prototyping

Each conversation stayed focused, but all of them pulled from the same underlying project context.

This let me move between areas of the system without losing continuity. I could pause work on one thing, come back days later, and still pick up where I left off.

Prototyping behavior before committing to code

Once I had a rough feature map and IA, I realized that feature lists and diagrams weren’t enough.

I could describe features in text, but I didn’t yet understand how they would behave. The fastest way to surface that gap was to visualize the features as actual screens and flows. I needed to see things.

From feature lists to behavior

Feature mapping and IA helped me understand the scope of the product, but they didn’t surface interaction complexity. The fastest way to close that gap was to visualize features as actual screens and flows.

Using quick prototypes to sharpen fuzzy understanding

As I shaped features and the IA in ChatGPT, I started visualizing each feature alongside that thinking.

I would take a feature from my notes, reason through it with ChatGPT, then materialize it as a rough UI. Once I had something concrete, I’d take snapshots back into ChatGPT and iterate again.

Some features didn’t survive this loop. Others changed shape once their behavior became visible.

This back-and-forth turned vague ideas into something more grounded.

Importantly it surfaced gaps in my understanding much earlier than they would have otherwise.

Freezing intent before prototyping

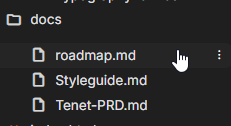

By this point, my IA and feature list were reasonably stable. I condensed all of that thinking into two documents:

a Tenet-

PRD.mdthat forced me to articulate the product’s intent, users, mental model, feature boundaries, and non-goalsa

Styleguide.mdthat outlined the high-level visual direction - colour, typography, and spacing rhythm

These weren’t final documents. Rather they were context anchors. Their role was to make sure that both my own thinking and the tools I was using stayed aligned as I moved forward.

I placed these files in a docs/ folder and used them as inputs during the prototyping phase.

Along with the .md files, I also created an instruction set for Google AI Studio. Without this setup, the prototype would drift or hallucinate. With it, the outputs stayed aligned to the system I was trying to build.

Committing to a prototype

I didn’t try to prototype the library with all components. Instead, I documented just one component - the Chip component, in depth.

That was enough to understand how the core ideas behaved: the playground, the learning views, the parity checks, and how tokens showed up across layers. Alongside this, I also built a few auxiliary pages like Foundations, Get Started (installation), and About to see how the system held together beyond the component playground.

For execution, I leaned on the two-tool workflow I usually resort to.

Design, reasoning and prompt authoring happened in ChatGPT.

Execution and refactoring happened in Google AI Studio.

Through this process, one clarification became clear. Tenet UI Studio worked best as a reference system - something you read, inspect, and copy from, rather than an installable npm package or a traditional component library.

Pushing the prototype

After that, I went a bit further than strictly necessary.

Out of curiosity, I spent time polishing the prototype. Nothing fancy though.

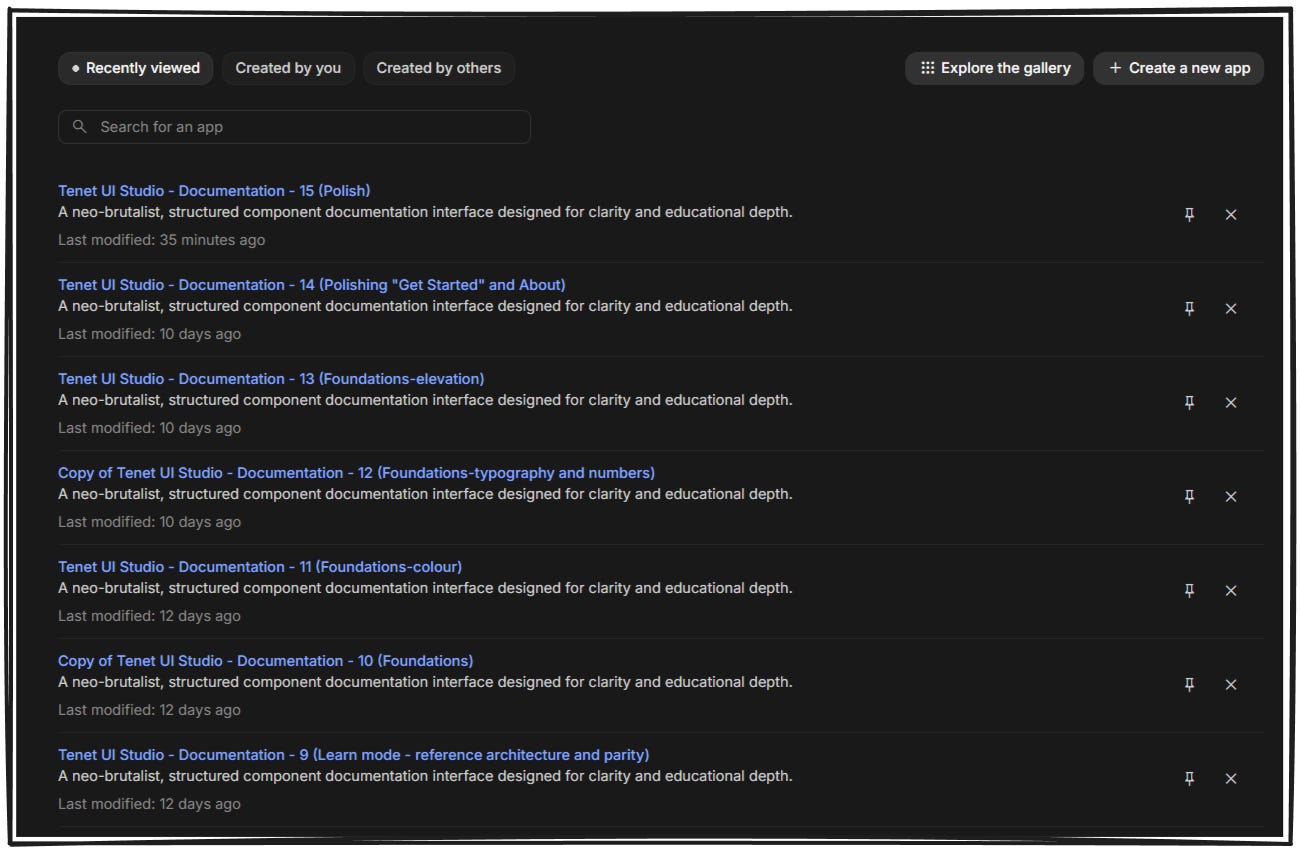

I also created multiple forks along the way. Having checkpoints made it easier to experiment without fear of losing work.

By the end, I had around fifteen forks of the same prototype. Each one represented a moment where the system felt coherent enough to move forward again.

Freezing intent before moving on

Once the prototype stopped changing in fundamental ways, it felt safe to move on to implementation in Cursor.

Closing notes

This workflow has been interesting largely because it’s shifted how I think about making things. Static artifacts are good at showing structure, but not always behavior.

Working this way moved everything closer to being dynamic. Ideas stopped living as diagrams and started showing up as interactions. When something was unclear, it didn’t stay abstract for long. It surfaced visually, in behavior, or in the friction of trying to explain it to the tools I was using.

In theory, I could probably do most of this directly inside Cursor. Over time, that may even become the default as tools get better. But for this project, having a GPT co-pilot outside of the implementation environment mattered. It gave me a space to reason, question, and discard ideas without feeling like I was already committing to code.

The split workflow - thinking and throwaway prototypes on one side, implementation in Cursor on the other, simply felt more comfortable at this stage. It let me explore without consequence, then switch modes once intent had stabilized.

I don’t see this as a settled answer. It’s more an open question I’m still sitting with. This is also my first time using Cursor seriously, and there’s probably room to collapse parts of this workflow into a single tool over time. That’s something I want to experiment with.

For now, this approach helped me build enough clarity to trust the next step. From here, the work shifts to execution.